The Commit Scope Matrix

A common advice is to put refactorings and new functionality into separate commits (and also into separate pull requests, if you’re into that kind of stuff1). I agree with that advice, and do recommend following it. The reasons are quite obvious when you think about it:

- It makes it much easier to understand the incremental changes (including during code reviews), both when they happen and far into the future.

- If you do asynchronous code reviews with pull requests, it can save both author and reviewer a lot of time: Extracted a method for clarity? That’s an easy LGTM. Replaced a 100-line method with a standard library call? That’s a single change.

- It makes it easy to revert a specific change, or to refer to a single change by commit ID.

- It facilitates continuous integration. Let others base their work on your refactored code ASAP—don’t make them resolve unnecessary merge conflicts after your feature is finished.2

In other words: Commits should be atomic.

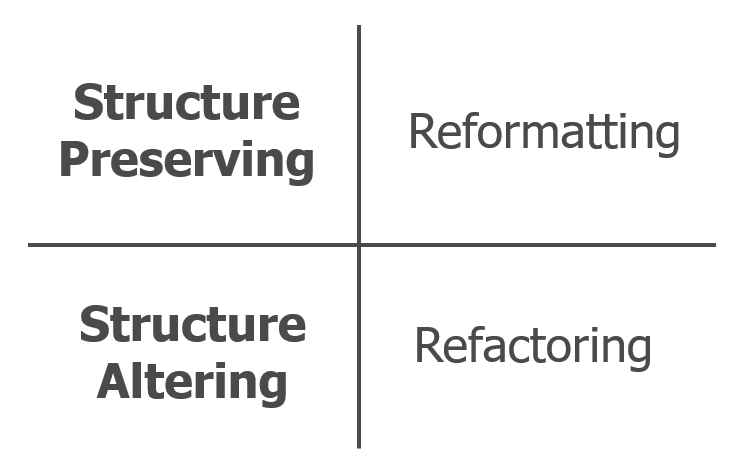

However useful that advice is, it is also incomplete in my view. In the same spirit as refactorings vs. functionality, I prefer to divide commits into 4 main categories.

Behavior Altering vs. Behavior Preserving changes

Let’s first review the definition of a refactoring:

Refactoring (noun): a change made to the internal structure of software to make it easier to understand and cheaper to modify without changing its observable behavior.

— Martin Fowler

Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code (p. 45), Pearson Education (Kindle Edition)

What actually makes those separated, intentionally scoped commits easier to work with is that they either change the structure but preserve the behavior (i.e., refactoring), or they change both structure and behavior (i.e., most new functionality and many bugfixes).

Can you implement new functionality without changing the structure at all? That’s an extremely rare case, akin to installing a plugin. Even with very diligent application of the Open-Closed Principle, it is almost impossible to not have to add a parameter somewhere or add new (even private) methods. The goal is to reduce the structural changes in the behavior altering commits to a minimum; i.e., those structural changes that only make it easier to implement the functional change are part of the refactoring, and those that enable the functional change are new functionality. Refactoring is defined as making behavior preserving structural changes to *existing *code. It does not imply that the addition of not-yet-existing code (like, e.g., adding a private method) is not a structural change.

Structure Altering vs. Structure Preserving changes

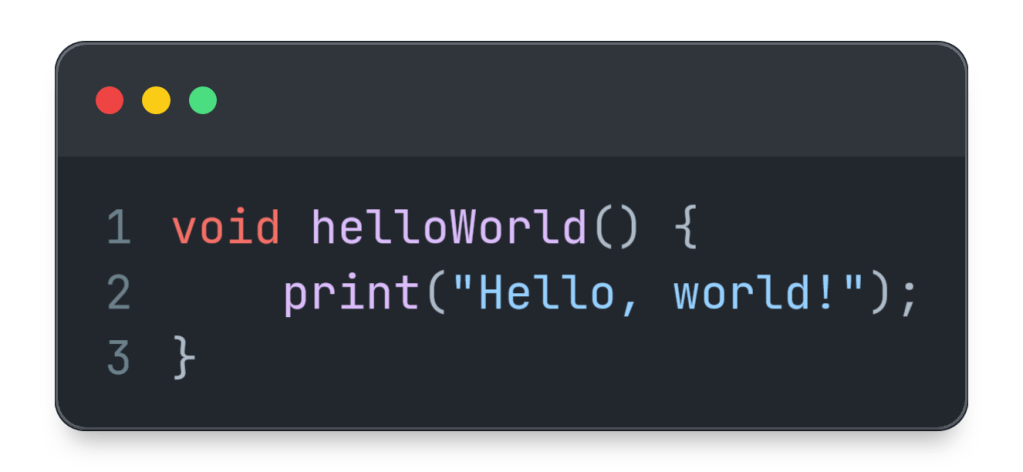

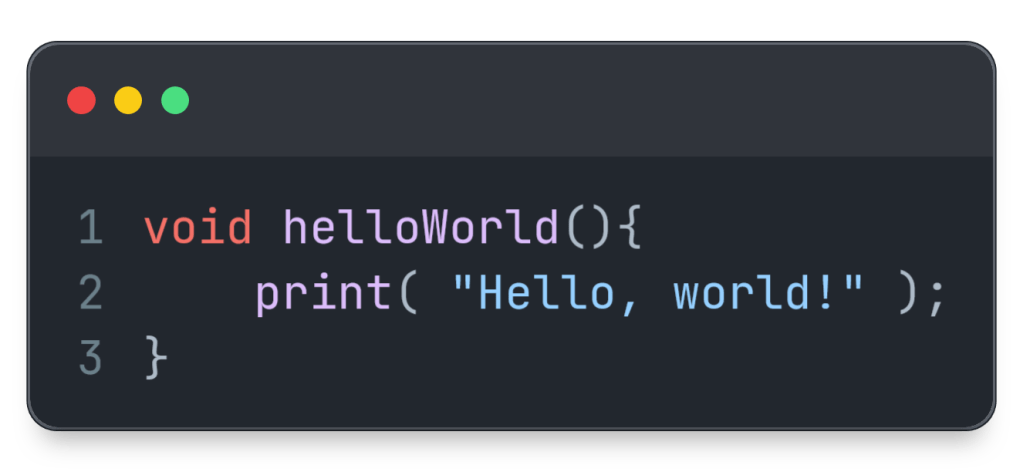

There’s a second dimension regarding the code’s structure. As we’ve seen, most changes alter the structure in one way or another, and the obvious difference is whether the behavior is preserved. Can you think of a kind of change that preserves both structure and behavior? This one’s less obvious, and it requires some leeway in how we define structure. For example, I consider the following two pieces of code to be structurally equivalent:

Even the syntax tree would probably be the exact same. This kind of difference is basically just a matter of style and can be fixed by a code formatter.3 Formatting this code is a change that I consider both structure preserving and behavior preserving. Contrast this to a refactoring, which is structure altering *and *behavior preserving. They reside on two extremes of the structural dimension.

However, reformatting is just one example. Maybe you can think of more kinds of changes that fit into this category. What about replacing an image?4

Last but not least we have changes that are structure preserving and behavior altering. In this category I classify for example configuration changes like enabling a feature toggle, replacing a service URL, making changes to .gitignore, or replacing a deprecated implementation with another one in a single step.5

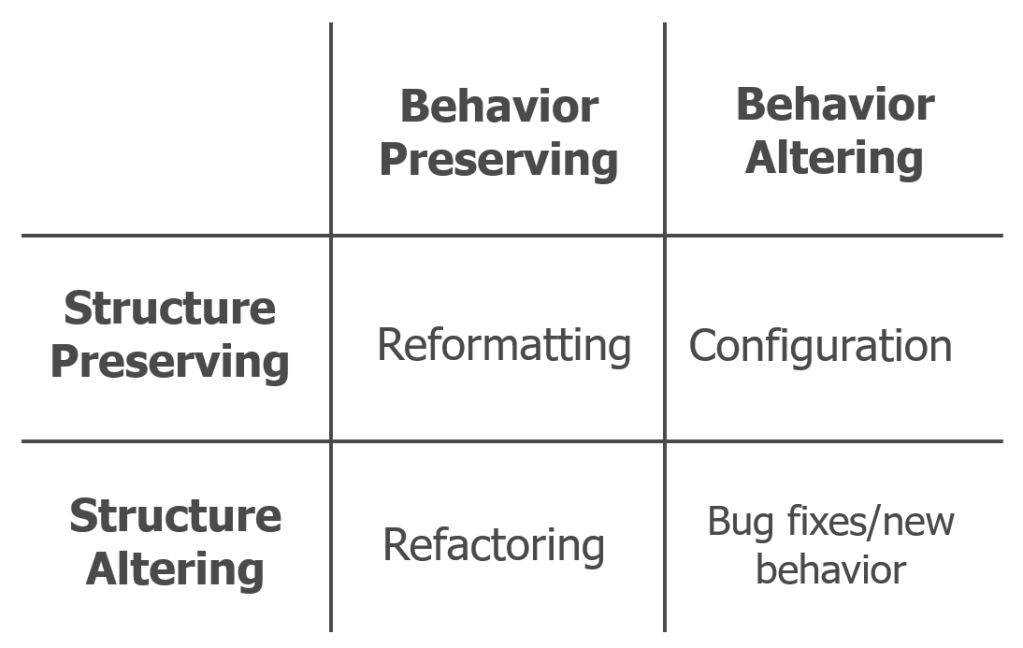

The whole picture

When considering both dimensions, behavior and structure, we can create a table, or matrix, that results in 4 categories.

- Refactorings are by definition structural changes that preserve the behavior.

- Feature work and bugfixes alter the behavior, and are often not possible without at least some structural changes, like addition or replacement of structure.

- Reformatting existing code preserves both structure and behavior, and it should be committed separate from even refactorings.

- Configuration changes change the behavior without requiring changes to the structure.

Some final words

As always, don’t be dogmatic about it. It’s just a general guideline that I find helpful to keep commits well scoped. But in cases where it doesn’t help, be flexible. If I refactor a method and see a missing space in another method, I might fix that misformatting in the same commit in such a trivial case. Or I might simply not add that space, as it’s out of scope and not urgent; it can be fixed the next time that other method is touched. It’s different when I see a whole block of code with wrong line endings, or with tabs instead of spaces (or vice versa, whatever is used in the codebase). In that case I would fix the format and commit it separately from any other changes.6 I would prefer the formatting to be handled by an automatic formatter (or even better, enforced with immediate feedback to the developer) for all committers in a project, but in an existing codebase where this was not done from the start, I don’t like whole files to be reformatted when new functionality is added. This should either happen separately and beforehand, or incrementally.

The inner cells of the matrix shown above, like configuration, reformatting, etc. are just examples. If running the formatter reorders methods and imports, it already might be considered structure altering. Some bugfixes might change behavior without really altering the structure (e.g., fixing an off-by-one error in a for loop). That’s why I prefer the categories on the outside over the concrete examples on the inside.

-

I generally don’‘t recommend pull requests and asynchronous code reviews in favor of CI\/CD, but that is out of scope for this article. ↩

-

More experienced developers usually cause fewer and smaller\/easier to resolve merge conflicts than less experienced developers, but the techniques and skills that prevent merge conflicts are not obvious; you can’‘t really count "prevented merge conflicts". When merge conflicts happen often, they can seem unavoidable. ↩

-

Although this should probably be handled by an automatic formatter, this does not change the fact that you can still run into ill-formatted code, especially in legacy codebases. ↩

-

There is some nuance in whether we consider a different image (different contents/size/quality) as different behavior. Don’t be dogmatic about it. It’s supposed to act as a general guideline, and in most cases it really is obvious. ↩

-

For example using branch by abstraction. If that is done in source code, we might not consider it a configuration change per se, but it can still be structure preserving and behavior altering. Another reason why I prefer these 4 more generic categories. ↩

-

Interactive or patch staging comes in handy in that case. If you’re not familiar with that, you can also stash any other current changes in your working directory before making that reformatting commit. A reformatting commit should normally not require a rubber-stamp pull request approval and can be integrated very quickly. ↩