Intro

In part 1 we prepared the JavaFX project for drawing 2D graphics and implemented some of the basic snake logic with TDD (test-driven development): Basic movement, colliding with walls, growing the snake when it eats the food.

Oh, and the two of you who have been waiting for part 2: Sorry for the delay! I could have finished and published it earlier, but I just didn’t want to. 😉

Test-driving the snake logic

Our last test looks like this.

@Test

void snakeGrowsOnNextTick() {

final var snake = new Snake(new Position(5, 5));

snake.grow();

snake.tick();

assertThatCollection(snake.positions())

.isEqualTo(List.of(

new Position(5, 6),

new Position(5, 5)));

}

We made it pass with this implementation.

public void grow() {

positions.add(positions.getFirst());

}

Basically we just duplicate the first (and only) segment to turn the snake into a 2-segment snake. This works for now, since we haven’t specified more cases yet, but it will not be enough for the playable game. Let’s continue with the next test.

Growing the snake (continued)

We don’t want the snake to grow immediately when it ate the food, but only on the next tick, so that the last segment “stays” at the same position as the rest of the snake moves a step forward. We can specify this as a unit test like this. Note that I renamed grow() to growOnNextTick() to be more explicit.

@Test

void snakeDoesNotGrowOnSameTick() {

final var snake = new Snake(new Position(5, 5));

snake.growOnNextTick();

assertThatCollection(snake.positions())

.isEqualTo(List.of(

new Position(5, 5)));

}

As expected, the test fails. There are many possible ways to make it pass, but the simplest one seems to be a simple boolean flag.

private boolean growOnNextTick;

public void tick() {

if (stepWouldCollide()) {

onCollision.run();

} else if (growOnNextTick) {

stepAndGrow();

} else {

step();

}

}

public void growOnNextTick() {

growOnNextTick = true;

}

private void stepAndGrow() {

final var oldHead = positions.getFirst();

final var newHead = new Position(oldHead.x(), oldHead.y() + 1);

positions.set(0, newHead);

positions.add(oldHead);

}

Maybe not the most elegant solution, but simple enough for now. Elegance is very subjective, and other properties like simplicity are way more important. With the tests specifying the expected behavior, we can safely refactor later on. Note that “later” here means within the next few minutes or hours, since we are still actively working on it. It is not the procrastination kind of “later” where we say “someone will refactor it some time in the future”, which usually does not happen.

Tip: Tests are specification by example

I’ve heard developers who’ve worked in large legacy code bases for a long time say that they know a lot about the code base and about the domain because they “debugged a lot over the years”. That is a very inefficient way of learning what the software does, especially if everyone on the team is expected to learn the code base and the business domain that way. A good test suite specifies the intended and actual behavior way more clearly than the code itself can, even when the code is written well, especially when the code changes and grows over time. This is even more important when the code is not written well, or when the problem it solves is complicated, resulting in a non-trivial implementation.

Note also that we are not yet resetting the boolean flag. That is unspecified behavior for now. We will definitely write a test for a typical game run later on, where the snake moves and eats and moves and so on. It is not specified by that last test, though.

Reorganizing the tests

A common anti-pattern is to have a test class named after the class it tests with just the Test suffix. Like SnakeTest for the Snake class. That test class then contains all of the tests for that class. We shouldn’t even be thinking about “testing a class”, let alone “testing individual methods”. What we are testing (and specifying) is the behavior of the snake.

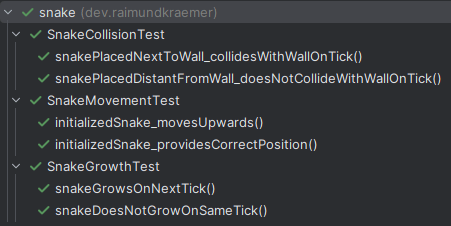

To better organize the tests into categories, we can create additional test classes now and move some of the tests there. Looking at the list of tests so far, we have multiple tests concerned with the basic movement, multiple tests for collision, and multiple tests for growth. More tests will probably be added to each of these categories, and more categories might emerge later on. So I reorganize the tests existing so far into these test fixtures:

SnakeMovementTestSnakeCollisionTestSnakeGrowthTest

This way we can easily change or add certain behaviors or just know where to look if we’re unsure about some part of the specification.

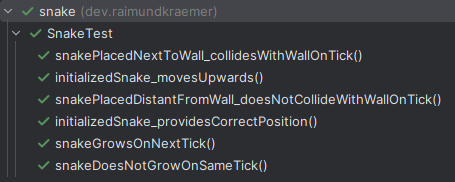

When running the tests, this is what the test results looked like before reorganizing the tests:

This is what they look like now:

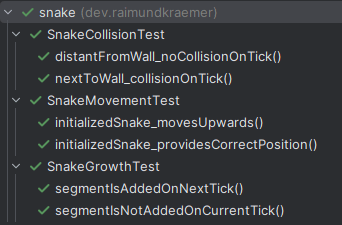

This gives us some nice benefits. First of all, we can now more easily run a subset of the tests for certain parts of the behavior. Secondly, we can now simplify some of the test method names, since part of the context is in the class name.

The new test method names look like this:

Already much clearer in my view and it becomes obvious where new tests are supposed to go.

Steering the snake

The snake is supposed to be steered by the player. The player input, be it keyboard presses, a joystick, a touch screen, or even voice input, is independent from the game logic. Instead we test at the level where we can just tell the snake a direction and the snake doesn’t care where that direction comes from. Of course, in our case the tests choose the direction.

We’ve decided earlier that the snake moves up at the beginning of the game until the player chooses a different direction, so now let’s add the other directions.

My failing test with the API for setting a direction looks like this:

@Test

void whenSettingDirectionToLeft_snakeMovesLeft() {

final var snake = new Snake(new Position(0, 0));

snake.setDirection(Direction.LEFT);

snake.tick();

assertThatCollection(snake.positions())

.isEqualTo(List.of(new Position(-1, 0)));

}

I generated the setDirection method and the Direction enum via the IDE (Alt + Enter in IntelliJ). Note that there is no reason yet to have any enum classes besides UP and LEFT defined in the enum as LEFT is the only one in use so far, UP must be set by default to keep existing tests passing.

The implementation looks like this for now (some changes omitted for brevity):

private void step() {

final var oldHead = positions.getFirst();

final var newHead = nextPosition(oldHead, direction);

positions.set(0, newHead);

}

private Position nextPosition(Position current, Direction direction) {

return switch (direction) {

case LEFT -> new Position(current.x() - 1, current.y());

case UP -> new Position(current.x(), current.y() + 1);

};

}

This already makes it clear how the other positions will be added in later steps.

Now, in the refactoring phase of the TDD cycle, I do a refactoring that is known as “Move method”. The nextPosition method quite clearly looks like it wants to be in the Position record. This is known as the feature envy code smell. I use the IDE (Refactor -> Move Instance Method in IntelliJ) to move the method.

IntelliJ kindly moved the method to the Position record:

public record Position(int x, int y) {

public Position nextPosition(Direction direction) {

return switch (direction) {

case LEFT -> new Position(x() - 1, y());

case UP -> new Position(x(), y() + 1);

};

}

}

It even updated all of the call sites, so that nextPosition(oldHead, direction) becomes oldHead.nextPosition(direction). Without the automatic refactoring we could have still done this in small steps with the safety of our tests and version control, but modern IDEs can do refactorings like this very quickly and safely.

Movement for longer snakes

So far I mostly specified the behavior of a single-segment snake, because that’s easier to start with and then build upon. Now I want to make sure longer snakes move as expected. That includes moving all segments in the correct direction, as well as moving the segments along the snake’s path and around corners instead of, e.g., moving all segment in the current direction if the snake has already taken 90 degree turns.

Here’s my first failing test for a longer snake. It’s easy to see in the assertion that the end of the snake’s tail is still vertically aligned and moved upwards, while the first half-and-a-bit moved in the zig-zag pattern resulting from the alternating direction changes.

void multiSegmentSnake_followsTheHeadsPath() {

final var snake = new Snake(

new Position(0, 0),

new Position(0, -1),

new Position(0, -2),

new Position(0, -3),

new Position(0, -4),

new Position(0, -5),

new Position(0, -6),

new Position(0, -7),

new Position(0, -8),

new Position(0, -9));

snake.setDirection(Direction.LEFT);

snake.tick();

snake.setDirection(Direction.UP);

snake.tick();

snake.setDirection(Direction.LEFT);

snake.tick();

snake.setDirection(Direction.UP);

snake.tick();

snake.setDirection(Direction.LEFT);

snake.tick();

snake.setDirection(Direction.UP);

snake.tick();

assertThatCollection(snake.positions())

.isEqualTo(List.of(

new Position(-3, 3),

new Position(-3, 2),

new Position(-2, 2),

new Position(-2, 1),

new Position(-1, 1),

new Position(-1, 0),

new Position(0, 0),

new Position(0, -1),

new Position(0, -2),

new Position(0, -3)));

}

Making it pass is simple. Instead of replacing the position of the first and only segment (for a single-segment snake) with the new position, I prepend (i.e., add to the beginning) the new head position and remove the last one. For a single-segment snake that is exactly equivalent: “Prepend the new position, then remove the old position” if there is only one segment is like replacing it.

So this:

private void step() {

final var oldHead = positions.getFirst();

final var newHead = oldHead.nextPosition(direction);

positions.set(0, newHead);

}

… simply becomes this:

private void step() {

final var oldHead = positions.getFirst();

final var newHead = oldHead.nextPosition(direction);

positions.addFirst(newHead);

positions.removeLast();

}

Because growing the snake is a special case of snake’s movement, where in addition to moving all segments forward a segment gets added to the end at the position of the previously last segment before the step, I also add a test for growing a multi-segment snake:

@Test

void multiSegmentSnake_growsTailWhileMovingTheRestForward() {

final var snake = new Snake(

new Position(0, 0),

new Position(0, -1),

new Position(0, -2));

snake.setDirection(Direction.UP);

snake.growOnNextTick();

snake.tick();

assertThatCollection(snake.positions())

.isEqualTo(List.of(

new Position(0, 1),

new Position(0, 0),

new Position(0, -1),

new Position(0, -2)));

}

As we can see from the test, prepending a new head position is equivalent to moving all segments forward and adding a copy of the previously last position, and we can choose whichever implementation is easier to implement/understand/change. From a domain perspective however, the snake definitely moves forward and the tail grows.

To make the test pass, this …

private void stepAndGrow() {

final var oldHead = positions.getFirst();

final var newHead = oldHead.nextPosition(direction);

positions.set(0, newHead);

positions.add(oldHead);

}

… turns into this:

private void stepAndGrow() {

final var oldHead = positions.getFirst();

final var newHead = oldHead.nextPosition(direction);

positions.addFirst(newHead);

}

Note how it actually got shorter, despite (or maybe exactly because of) being more general. As the tests get incrementally more specific, the implementation evolves to become more generalized.

Next, I write a test to specify that the command for changing the direction should be ignored if it’s not a 90 degree change; except for a single-segment snake, since the actual purpose is to prevent the snake from moving backwards “into itself”, so the head segment should never be able to move into nor collide with the second snake segment. For example, if the snake is currently moving upwards, it is not possible to move down on the next tick, only left or right, just like setting the current direction again has no effect. This is simply a rule of the Snake game as I know it, and I don’t know how it could be any different. My failing test for a snake with two segments looks like this:

@Test

void multiSegmentSnake_ignores180DegreeDirectionChange() {

final var snake = new Snake(

new Position(0, 0),

new Position(0, -1));

snake.requestDirection(Direction.UP);

snake.tick();

assertThatCollection(snake.positions())

.isEqualTo(List.of(

new Position(0, 1),

new Position(0, 0)));

snake.requestDirection(Direction.DOWN);

snake.tick();

assertThatCollection(snake.positions())

.as("The snake is expected to keep moving upwards, because changing the direction to down is not " +

"allowed if the snake's head would need to move to the position occupied by the snake's " +

"second segment.")

.isEqualTo(List.of(

new Position(0, 2),

new Position(0, 1)));

}

Some things to note:

- The test has a description which explains the “why” behind the test case. This description is visible in the test definition as well as in the test result in case the test fails. This is much better than a comment, which would not be visible in the test result.

- We are testing whether the snake moved upwards as expected by checking where the snake ended up, not by checking which direction it has set internally. We want to test the behavior, not the internal state.

- While we want to assert only one piece of behavior per test, in some cases we might still use multiple assertions to test a single behavior, especially if that behavior has multiple steps, like in this case.

- I renamed

setDirectiontorequestDirection, because I find that makes it clearer that it is a fire-and-forget request to the snake, and the snake knows whether it can fulfill that request. In this case I don’t even care about the result, because the resulting behavior will be visual feedback to the player rather than something to be handled by the caller of this method. Whichever means of input the player uses (and we don’t care about specifics if player input here), the player can request as many direction changes as they want. They can even change the direction multiple times per tick since the consequence of the direction change will only have effect on the next tick when the snake executes the next step.

This is how I implement the behavior specified by the test:

public void requestDirection(Direction direction) {

if (isDirectionChangeAllowed(direction)) {

this.direction = direction;

}

}

private boolean isDirectionChangeAllowed(Direction direction) {

if (positions().size() == 1) {

// A single-segment snake can change to any direction.

return true;

}

// A multi-segment snake can not move "backwards" where the head segment would need

// to move to the position occupied by the second segment.

// E.g., the snake can not move down if the second segment is below the snake's head.

final var head = positions.get(0);

final var secondSegment = positions.get(1);

return switch (direction) {

case DOWN -> head.y() <= secondSegment.y();

default -> true;

};

}

I simply check whether the second snake segment is below the snake’s head. If it is, then the request to change the direction to DOWN is ignored. Other directions will be added in the next steps.

At this point, I hope the general concept is clear, and I will add the remaining logic “off the record”. This will include the remaining directions and things like self-collision of the snake. Feel free to follow along with the commit history in the GitHub repository.

Connecting the graphics to the logic

At this point, we have implemented the snake game logic completely test-driven. While it’s not guaranteed that there won’t be any bugs by now, they would be more like undefined behavior because we would simply have forgotten about certain situations or edge cases. If that’s the case, it should be relatively easy to add a test for the respective behavior and close that hole.

While one might expect that typing the tests took additional time, typing out a few lines of example code is very quick, especially with IDE completion. What’s easy to miss is that there was little to no debugging. Each test kind of debugs a part of the code “in advance”, repeatably and in milliseconds. The biggest portion of the time per test goes into thinking about the expected behavior and how to design the API, which we would need to do anyway even without tests (or might actually do less of).

Now we’re ready to finalize the game with some simple graphics. Since we did not depend on the graphics while implementing the logic, we have a lot of options in how we want to design the looks of the game. We could use animations, since the time between ticks can be used for animating or simply interpolating states, or we can simply redraw the state once per tick.

I actually wrote this part 2 more than a year ago and had the draft lying around half finished, since I never got around to finish it with some nice graphics. Maybe I will add a part 3 at some point, but no promises. I hope you learned something and enjoyed it. Feel free to fork the repository and finish this game yourself, including some nice graphics.